Nashulai Maasai Conservancy is part of the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, home to some of the world’s greatest biodiversity. Situated in the African Great Rift Valley, the world-renowned ecosystem includes vast open grasslands, riverine forests, woodlands, swamps, non-deciduous thickets, and rocky escarpments.

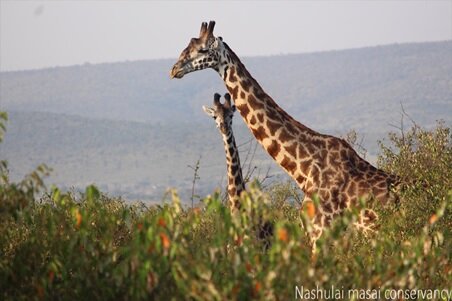

It is across this ancient land that each year over 2 million animals— wildebeest, zebra, and gazelles— set off together on their epic Great Migration across almost 3000 kilometres along the routes they have used for millennia, following the spring rains in search of fresh pastures and water. Lions, leopards, elephants, buffalos, rhinoceros, giraffes, and cheetahs call this land home; hippopotamus, crocodiles, and fish live in the rivers; and thousands of bird species could be found in the grasslands, swamps, and woods.

This is also the birthplace of humanity, the land where Homo Sapiens evolved. And thousands of years ago, it became home to the Maasai people.

“The biggest challenge facing wildlife today in Kenya is lack of space.” - Nelson Ole Reiyia

Our culture is fully connected to the diversity of our land. All of our traditional songs and stories are about our animals. Over the centuries we have learning many lessons through observing them which our Elders have passed on to future generations until this day.

The Maasai lived sustainably with other species for centuries, rotating their grazing herds of cattle on communal land, respecting both it and the wildlife with whom they lived in carefully nurtured harmony. Our Elders speak of when we raised our herds alongside the great animals that roamed freely, and of when elephant herds would come here to birth their young. That balance was completely upended by the rapid changes of the last 100 years.

Colonial land-use practices first relocated whole families, and later subdivided the communal land among them; fencing criss-crossed the plains, and the wildlife began to disappear as migration corridors were fenced off. The animals and their ancient migration routes do not follow man-made boundaries, and while much of the ecosystem was “protected” in the Maasai Mara and Serengeti national parks, much was left unprotected, and deeply vulnerable to poachers. Streams and rivers, polluted and deforested, became undrinkable. Over the past 40 years the human population throughout Kenya has grown over 4 times, while the wildlife population has declined 75%.

By 2015 our once open lands had declined into a collection of small fenced-in plots that could barely support our people. The important 5000-acre area that is now Nashulai, long recognized by scientists as “a critical wildlife corridor” for elephants and for the Great Migration, had been closed off.

And importantly, the Maasai had lost their connection to the wisdom of the land, to the wisdom of place, and—increasingly separated from their traditions or a way of life that could provide both pride and benefit—were drifting into sterile poverty or leaving the land for the city. We knew that without the involvement of the community, there could be no regeneration.

We knew we had to save this land for ourselves—but also for future generations.

“The space that can be available is with the communities, but communities can only welcome animals into their land if they are also getting benefits.” - Nelson Ole Reiyia

When our Elders gathered to found Nashulai in 2016 there was, by comparison even to what we remembered from our childhoods, virtually no wildlife. Inspired by Nashulai’s co-founders, Nelson Ole Reiyia and Ric (Olomunyak) Young, the Elders and leaders of the communities throughout the area met in our enkiguena, our traditional community gathering in a circle, to advance the discussion. It was decided we would tear down all 25 km of fences on our territory and turn our land back into a commons—communally managed by all in the interest of each other, the wildlife and the whole ecosystem. Our residents would return to our traditional rotational grazing schedules that (supported by modern science) would allow for sustainable grasslands management. And in a break from centuries of Maasai tradition, we stopped our retaliatory killing of predators that attacked our livestock, encouraging communal respect between our species.

The result was that Nashulai became again a critical connecting corridor, allowing the wildlife protected passage between the Maasai Mara National Reserve and other community conservancies to the south, north and east. By implementing sustainable rotational grazing, the grass cover, in just one year, returned across Nashulai. The animals voted with their feet. During our first Great Migration over 10,000 wildebeests and zebras passed through, numbers our Elders couldn’t recall in decades! The elephants returned to their ancestral nursery with 5 herds quickly taking up residence. Thanks to the protection of our scouts and rangers, giraffes and impalas also began birthing in Nashulai, making our conservancy their home base.

INCREASING CONSERVATION EFFORTS: We’re keenly aware of the immediate threats to conservation, plus the dangers from poachers who are resurfacing in this economic climate. We don’t want to lose the remarkable conservation gains we’ve made in such a short time, which included removing the fences to re-open the old migratory routes and eradicating poaching, both of which have had an immediate effect on the return of wildlife.

The Rangers & Scouts—we call them “our Maasai Warriors of the 21st Century”–are the backbone of our conservation efforts, now assisted by our Warriors for Wildlife Protection, guarding against human-wildlife conflict and monitoring the animals such as the elephants, cheetah’s, lions and other at-risk species.

We are now home to approximately 500 zebras, 500 gnu, 200 wildebeests, and thousands of warthogs. Our Maasai giraffe population is one of the largest in the eastern part of the Mara ecosystem. In the last two years, around 50 elephants have been birthed on our land, with herds (average size 20) passing through and taking up temporary residence every few weeks so their young can feed on our acacia woods. The birds are returning to live in those woods, along the banks of our Sekenani River, and in our grasslands and forests.

The return of herbivores has also led, in the natural ways of life, to the return of predators. We are home to approximately 25 lions and for the first time in living memory approximately 10 cheetahs have included Nashulai in their range. At least 3 highly endangered and illusive African wild dogs have been spotted at Nashulai.

Our Elders are amazed to see our land returning so quickly to how it used to be. The success of the Nashulai model of conservation is a source of immense pride for our community. Our Maasai culture and spirit is rehabilitated as we rise with courage to meet today’s challenges.

Our community is empowered that WE are protecting OUR land and OUR wildlife, saving it from ecological collapse. Our self-determination to rise out of poverty is inextricably connected to the health of the land: people, wildlife, cattle, nature, respectfully linked here at Nashulai, ancient wisdom combining with modern science.

We are young and need support still. But we believe we are building a model of what’s possible for the regeneration of our world.

We’ve been inspired by the resilience with which the community rose to the challenge of Covid. How, even during this crisis, we’ve taken the first steps towards fully restoring the degraded Sekanani River.

As stewards of the land, we now see the toxicity in our water and the degradation of our ecosystem not as threats, but challenges that we ARE overcoming.